|

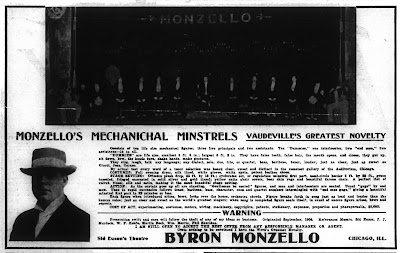

| A Variety ad for Byron Monzello's Mechanical Minstrels |

Vaudeville's so-called "automatic" or "mechanical" minstrels were dummy acts. The minstrel part of the dummies' act—the singing and joke telling—was provided by phonograph recordings. These automatic or mechanical minstrels, which appeared in vaudeville in the 1900s and possibly even earlier, were kind of like a low-tech precursor to the animatronic characters that later featured in places like Chuck E. Cheese, Showbiz Pizza, and Disneyland.

I first read about the automatic minstrels in the books of Joe Laurie Jr., a former vaudevillian who wrote or cowrote two histories of vaudeville in the mid-20th century: Show Biz: From Vaude to Video (1951) and Vaudeville: From the Honky-Tonks to the Palace (1953).

|

| Gane's Manhattan Theatre |

In these books, Laurie mentions a couple of automatic minstrel acts. In Show Biz: From Vaude to Video, he says that "William Gane introduced the first (and last) All-Automatic Minstrels at the Manhattan Theatre in 1908." Laurie describes the act thusly: "Outside of one live interlocutor, all the minstrels were dummies with gramophones concealed inside, telling jokes and singing songs upon cue."

In Vaudeville: From the Honky-Tonks to the Palace, Laurie elaborates a bit further on Gane's act:

"The Automatic Minstrels ... played at Gane's Manhattan Theatre (where Macy's is now). This one had a live interlocutor; the rest were dummies, whose jokes and songs were done via phonographs. Didn't do so good."In the same book, Laurie describes an additional automatic minstrel act, despite his previous book's claim that Gane's minstrels were the only one of their kind. This other act is identified as Monzello, "a minstrel show with dummies on the stage and the gags done via phonograph." Laurie added, "Kinda crude but a novelty."

Monzello was actually Byron Monzello. The 1908 ad for Monzello's Mechanichal [sic] Minstrels at the top of this page describes the act as "ten life size mechanical figures; three live principals and two assistants." The ad also describes the dummies: "They have false teeth, false hair, the mouth opens, and closes, they get up, sit down, bow, the heads turn, shake hands, make gestures." The ad claims that the dummies "talk any language." A photo of the minstrels is included, but it's too dark to reveal many details.

Also in 1908, Variety printed a letter from Byron (misspelled as "Bryon"), who wrote in reply to a review of Gane's act that Variety had published in a previous issue. Monzello's letter read:

I see in Variety (August 22) under "New Acts" a review on "William Gane's Automatic Minstrels'" at the Manhattan Theatre, New York. This is a direct steal of my act. I will furnish affidavits I originated "The Mechanical Minstrels" in September, 1904, at Indianapolis. Not then satisfied with results, I continued experimenting until September, 1906, when my act was completed, but other business matters prevented me placing it in vaudeville.

Enclosed you will find correspondence from prominent managers showing the act has been played at Riverview Park, and in existence over one year.Despite Monzello's claim of being the first to create a mechanical minstrel act, earlier mentions of similar acts can be found in late-19th century newspapers. The phonograph was invented in 1877, so it's possible that these early mechanical minstrel acts incorporated phonograph recordings too.

Even if it's true that Gane stole Monzello's act, vaudevillians stole each others acts, jokes, catchphrases, skits, and gimmicks constantly. In those days, a performer could steal another performer's act wholesale and take it to another part of the country without anyone easily finding out. In Vaudeville: From the Honky-Tonks to the Palace, Laurie gives a number of examples of well-know television and movie personalities of the post-vaudeville era who "borrowed" from earlier vaudeville performers.

No comments:

Post a Comment